OPENING

FRIDAY 18.10.02 AT 8PM

PRESENTATION

19.10.02 – 31.08.02

The research project Legal Space/Public Space will be carried out in four stages, from 18 October, 2002 to September, 2003:

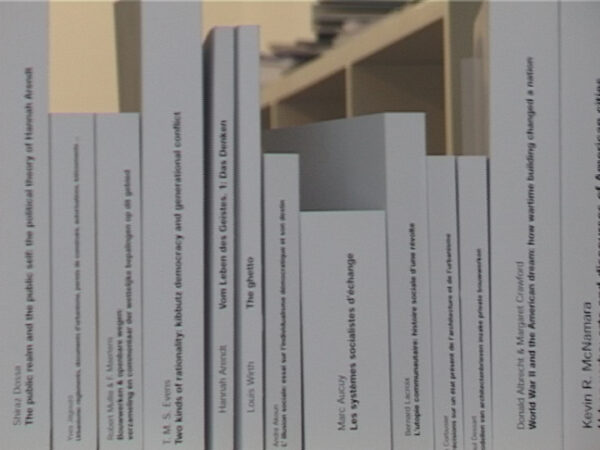

1. ongoing documentary center;

2. a cycle of workshops and conferences;

3. organizing a series of public space interventions;

4. the publication of the entire project, which will recapitulate all the information for the three preceding stages.

As its name suggests, the “Ongoing Documentary Center” is a space for study and for consultation that will grow little by as the research project, Legal Space/Public Space progresses. At this opening stage of the project, we shall call it a “presentation” rather than an “exhibition” in the classical sense of that term. This is why we have found it to our advantage not to post a complete and final list of artists related to the project. To do that would indeed go against what gives the project some of its specificity because it would overshadow the project’s open-ended character. Below, you’ll find a list of the artists we invited for the beginning of the project.

Beware of the shady foxes!

A citizen

walks across town, his critical gaze founded on a resolutely constructive wish. He scrutinizes Seville, his beloved native city. No one consulted him to find out if he liked the white house on the Place d’Espagne or if the new lines designating the pedestrian sidewalk on Sierpes Street are pretty and to his taste. Is that important? and, if so, for whom? An idea keeps going through his head. The idea, stronger than desire, is without a doubt of the order of need. Santiago Cirugeda wants to mount a scaffold on the historic center of the polis. He applies himself to it. He chooses a wall and writes graffiti on it. Later on he calls the Town Hall, apologizing for his act and offering to repaint the wall to make amends. He then inquires about the permits required for him to carry out his own project, that is, to gain permission to mount a scaffold against the wall and thus atone for his “vandalistic” act. Santiago mounts the scaffold as soon as he obtains the permit. It is by no means trifling. Completely closed, enveloped by real walls, it comes towards you like an architectural outgrowth of the building. It would be accurate to say that Santiago added a new room to the building. Better still, we could say that, through his astute act, Santiago succeeds both in pointing out the major problem with the lack of opportunity for citizen involvement in the historical centers of cities and in suggesting a possible solution. He placed a real juridical weapon at our disposal, a tool that allows us to act while “obeying the law,” that is, while in accordance with the regulations which govern and delimit the use of public space. Whatever interpretation one may have of the situation, Santiago’s intervention indisputably vindicates the right to “liberty” in the city. Architect, artist, art critic-doesn’t the term “attitude” capture the difference between these three aptly enough? The polyvalent activity of the Spaniard Santiago Cirugeda suggests an equivalence. His activities formulate, sometimes even formalize, the equation of a public space understood as a juridical space that can be played with as well as transgressed and subverted.

__________

An individual; a citizen

is privy to a precious bit of information, and she has all intentions of using it: ships are governed by the laws of the countries they come from and not by the laws of the counties they are moored in. Our citizen is Dutch, her name is Rebecca Gompers, and she is a doctor. She works. Together with her group, Women on Waves, she dedicates herself to finding operational solutions that allow them to practice abortions-legally!-in countries where abortion is forbidden. Despite undeniable advances in this area, we all know that “voluntary interruption of pregnancy” is not yet as globally available as one would wish. Ireland is a good example, and a pertinent one since it is there that Rebecca’s first actions will take place.

A completely new solution from the juridical point of view sees the light of day. A solution that will allow Irish women to have abortions close to home despite the national decree that still forbids abortion. As it turns out, the article of the law outlines the methods for preventing abortion on national territory, that is, on land, but no one has as of yet bothered to pass a legislation forbidding it at sea. And, far from the coastlines, international waters open a new path for liberating this practice. This same liberty which associations like Greenpeace had to claim to run their activities adequately. An undeniable juridical weapon. The group Women on the Waves sets up a clinic on a boat heading for Ireland. This hospital, governed by Dutch law, offers Irish women the possibility of having abortions in a safe and perfectly legal way.

__________

A survivor; someone who refuses to call himself a citizen

decides no longer to belong to any social space. He leaves his city and decides to settle in the woods. We are in the United States, in 1845. The bases for a public space had been more or less established for quite some time in most of our big, Western cities. Henry David Thoreau intends to leave all this behind: the monotony of big cities, the injustices they give rise to, the tiresome obligations. He distances himself from the city and sets out to create his own habitat far away from the functional and fundamental constraints which in the city inhibit his conceptual edification. He plunges, consciously, into an autarchic life which he will describe in his book Walden, published in 1854. Just some years before the publication of Walden, Thoreau had written an essay that became a landmark overnight: Civil Disobedience (1849), a major influence on thinkers as diverse as Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr. Originally entitled Resistance to Civil Government, the essay is a declaration of the right to protest. Thoreau describes his imprisonment due to his failure to comply with his duties as a citizen. The author had been put in jail for refusing to pay a poll tax as a way of showing his objections to the war with Mexico. Thoreau was freed when his friend and mentor-Ralph Waldo Emerson-paid the fines which also annulled the act of protest. Civil Disobedience is a plea for the right to protest.

__________

Protesters; citizens

post their discontent.

__________

The shady foxes

slip away.

__________

__________

__________

__________

more or less marginal, more or less official, they index the construction of a space communally named “public”-its acceptance boils down to saying that it belongs to everybody …

__________

sometimes they deviate from the law, sometimes they use its founding principles.

__________

The owners?

Brussels, 2000. The association Agency is invited to build a room in one of the capital’s metro stations. It chooses a place close to the ticket booths. It requests permission to have a part of the space under its command. Using red lines, it marks out a 6,36 x 5,28 rectangle on the floor. On a nearby column, Agency sets up a small display offering to passers-by a red pamphlet comprising a legal decree. No one notices the red lines. Basically, these lines are very much like the ones situated a bit further down, or the ones situated close to the escalators a few meters away. Same size, same red. These lines serve to indicate to us that we have entered the metro, and thus they indicate our “engagement” in a public space, the beginning of a norm that we are expected to respect in our roles as citizens. Conversely, the inside of the rectangle created by Agency is the polar opposite of the conventions stipulated by the law. The lines outlining the rectangle indicate that the law’s principle of application is only operative outside its area. In fact, the center of the rectangle remains outside the law: it provides us with a temporary juridical exception, a sort of void, a few square meters of permissiveness.

The world. Position: N57o 10′ 43,3″ E 010o 05′ 1-3,1 Manual for Land is a project of the Danish group N55. As a result of this project, we are now able to arrange spaces in various parts of the planet. N55 takes care of communicating the existence of these spaces as well as their location through the internet. Today, the group has eight spaces “under its command.” Position: N 52o 18′ 19,7″ E005o 32′ 11,7″. As their web-site indicates, each and everyone of us can become the user of a piece of land. Position: N 57o 20′ 04,5″ E 010o 30′ 56,5″. Little by little, Land keeps growing. Anyone wishing to to add pieces to the “puzzle” is welcome to do so. All you must do is inform N55 of the location of your property so that N55 may include it in its “Internet-Catalogue.” The person donating the land must be able to guarantee that the land can be used by a third party. Those participating in the Land project remain, however, owners of their land. Position: N56o 59′ 55″ E009′ o19′ 33,7″. All the pieces of land are endowed with a structure within which we can find a Land manual. Position: N33o 10′ 43,9″ E -117o 14′ 26,7″. Manual for Land is a way of questioning the ownership of land, earth, and space. Position: N33o 10′ 43,9″ E -117o 14′ 26,7″.

__________

???????

The city: public, physical, social, and political space. In 1995, the artist Christophe Terlinden starts working on the clock of the old station of Brussels’ Léopold neighborhood, known today as Luxembourg station. The neighborhood as a whole is in a state of transition, on its way to becoming the symbol of the presence of European institutions in Brussels. The neighborhood’s new layout makes it seem like a new Wall Street in which only institutions and offices would have the right to exist. The slow process of dehumanizing the neighborhood is almost accomplished, and many of its inhabitants have already moved to other parts of the city. The station is also being renovated. And the clock on its façade seems to have been mercilessly abandoned, like everything else. Christophe Terlinden meets with the station manager to request permission to work on the clock. He cleans it and then paints it gold yellow, as if to confer upon it the look of an “emblem for the future.” Then, having restored its dignity, he repairs it. Christophe has essentially restored tempo to the neighborhood. He re-installed “time,” which had been completely forgotten in a project of depopulation that had been conceived in, and marked by, complete disregard for social ties.

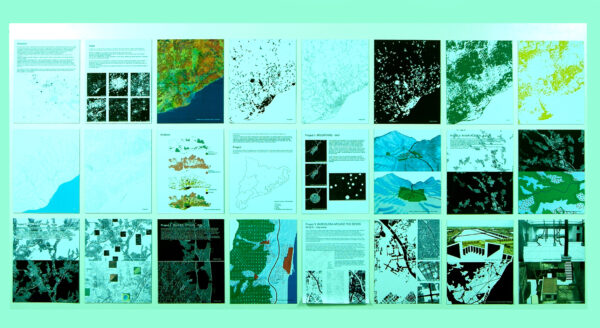

That same year, the artist Lara Almarcegui starts to wonder about the urban planning outlines of her city of residence: Amsterdam. There she is confronted with a public space based on an excess of rules, the lack of free spaces for the citizen, and the inherent difficulty of transgressing the rules. She imagines writing about the history of this city. She sets out to find the still non-invested spaces, the pieces of land that have not yet been built upon. She decides to collect these in a new map, the Wastelands map Amsterdam: a guide to the empty sites of Amsterdam. This map of the empty lots is a big, recto-verso sheet: on one side are marked the locations of the different empty lots while on the other side there are photographs of some of the lots accompanied by introductory texts. Once the map is printed, the information it contains is inevitably in danger of becoming false, outdated. Little by little the empty lots are transformed, and the map captures a trace of this transformation while redefining the notion of entropy with its empty spaces as a measure of disorder.

By offering us a selection of the constitutive elements of the city’s future, Lara illustrates the very principle of the city’s evolution. Although the artist points out the absence of a physical space in the city, she more than anything instills in us a sense of its enormous potential: un-designed spaces, semi- or completely virginal.

1999. The artists Simona Denicolai and Ivo Provoost are invited to make a work in the public space by the Mission d’art contemporain à la Ville de Saint-Nazaire. The entire context seems, a priori, favorable for an artistic intervention; in the official logic, such interventions could be useful should the city want to give itself a new image. And that is indeed the case. Projects designed to make the urban landscape more attractive reveal the desire common to politicians to efface the harshness of the city, which reflects the social reality found in harbor complexes. The two artists have understood the stakes and the symbolic import of their intervention. But, instead of effacing this reality, they decide to use it. They start visiting the local businesses which, consciously or not, participate in the edification of an identity, of a global image: in short, the city. They request from these businesses “tangible” tokens of their activities: a piece of a car body, shingles from a convoy. Their write down their request in a contract named “Logos,” which is simultaneously the title of their project and a generic term for the commitment of its signers: the businesses, the visual artists, and the city of Saint-Nazaire. “Logos” stipulates that the sponsor “lends one or more industrial parts … in the context of a play-mobile ….” Ready for action, Simona and Ivo start to put these “objects” in the city’s major intersections. On each of these “play mobiles” they put the logo of their company of origin. The public space is thus designed by the private and punctuated by the image of a local industry, in the transaction of a “nascent communication”.

__________

__________

working in its interstices.

__________

furnishing possible readings.

__________

An activist; a citizen

is walking down the street. Close to her house there is big area with an enormous hole, a clear harbinger for the imminent construction of a parking-lot or of some other project of subterranean paths. On the eve of Brussels’ “conge du bâtiment” (a one month official holiday for all the construction workers of public works), the excavation continues and leads one to imagine the worst. Nathalie Mertens must intervene, in case no one else does it.

The artist arrives on the scene at night bearing an amusing load: 300 pots of planted sunflowers. When the city wakes up, it finds it has a new garden which will flourish thanks to the respect of the neighbors. Baptized by the media as the “sunflower case,” this work illustrates a way of using the city that goes beyond the framework of a simple intervention. The artist strives for the enlargement of the public space, and in this case she even creates new a one! Moreover, if the empty lot is private property that has an impact on public space, Nathalie has succeeded in upsetting this given by touching on the sacrosanct right to property. The citizen is invited to enjoy a space that has become, from now on, both public and private. In this manner, Nathalie gives a new impetus to the city at the same time that, through her work, she outlines the shortcomings and malfunctions of a city, its holes and its square meter left abandoned. And when, later on, she decides to make use of the other empty lots of Brussels to plant more gardens, she once more touches up, poetically, the negative cartography of her city.

__________

Beware of shady foxes!

__________

__________

Eva González-Sancho

Brussels, October 2002